Galatians 1:8 But even if we or an angel from heaven should proclaim to you a gospel contrary to what we proclaimed to you, let that one be accursed!

1:9 As we have said before, so now I repeat, if anyone proclaims to you a gospel contrary to what you received, let that one be accursed!

1:11 For I want you to know, brothers and sisters,that the gospel that was proclaimed by me is not of human origin;

1:15-16 But when God, who had set me apart before I was born and called me through his grace, was pleased to reveal his Son to me, so that I might proclaim him among the Gentiles, I did not confer with any human being,

1:23 they only heard it said, "The one who formerly was persecuting us is now proclaiming the faith he once tried to destroy." (NRSV)

"What is the gospel? The Greek euangelion has come into English by way of Latin and French as evangel (cf. German Evangelium, French evangile). The more common gospel derives from the Old English godspel "good talk," and--like the popular phrase good news--is based on the etymology of the Greek word....

"The gospel of Christ is accordingly an abbreviation that points to the content of the gospel, which has already been alluded to in Paul's additions to the opening (vv. 1b, 4). Thus the gospel, which in his [Paul's] view is perverted by the troublemakers in Galatia, is the proclamation that God has created salvation in the event of Jesus' death and resurrection....For Paul this understanding has consequences in regard to the law and circumcision, which he will then discuss in the following chapters....The foundation of his [Paul's] argumentation is primarily the content of the gospel, the Christology. Subordinated to it are the Scriptures (for him, only the Old Testament) and the history of the gospel in Paul's own history from his conversion before Damascus to his activity in Galatia." (Dieter Lührmann, p. 12-13, Galatians 1992)

Given enough time and energy, I hope to blog a bit through the book of Galatians....we shall see....in any event, something strikes my fancy as I read through these opening verses in Galatians. Paul is an evangelist. The Greek words that we translate as "gospel" and "proclaim" (or "preach") are very similar, euangelion and euangelizo, respectively. Why this is interesting is the link between proclamation and content, the relation between the way in which one is proclaiming the gospel and the gospel that is being proclaimed....and....of course.....that makes me think of my own prior background as an evangelical in the U.S.

Given enough time and energy, I hope to blog a bit through the book of Galatians....we shall see....in any event, something strikes my fancy as I read through these opening verses in Galatians. Paul is an evangelist. The Greek words that we translate as "gospel" and "proclaim" (or "preach") are very similar, euangelion and euangelizo, respectively. Why this is interesting is the link between proclamation and content, the relation between the way in which one is proclaiming the gospel and the gospel that is being proclaimed....and....of course.....that makes me think of my own prior background as an evangelical in the U.S.

From my experience in evangelical circles there has been a very rapid decline in enthusiasm for evangelism. I think that this creates a bit of an evangelical crisis. Evangelism, as it has been defined in the last fifty years or so, basically reduces to proselytizing: convince others that Christianity (or "a relationship with Jesus/God" as the contemporary language goes) is the religion of choice. As I said, from my experience, the younger set is kind of losing its steam for this kind of approach. So, most people really don't engage in proselytizing, at least not in a direct person-to-person mode.

To address this crisis of evangelism, the evangelism of choice these days is marketing manipulation. (Yes, I am negatively predisposed!) Contemporary evangelism has taken the form of media to the masses. Evangelical film, literature, and staged church performances attempt to persuade the nonbeliever of his or her need to become a believer. This seems more subtle to today's evangelical--rather than "preach" to people and put them off with a direct confrontation (as they did in the good 'ole days), the contemporary evangelical prefers the subtle, nonthreatening methods of modern media. In my opinion, however, it is simply a manipulation tool like all other manipulation tools in today's media age. This is evangelicalism in the digital age, evangelism as advertising, manipulation, and marketing.

My observation at this point is that we need to evaluate the link between the gospel message (euangelion) and the "proclamation" (euangelizo). Simply put, the reason that so many evangelicals cringe at the thought of direct evangelism is that the message itself is so threatening, uncomfortable, and just plain awkward. Things can get a bit uncomfortable when you mention to people, "Uh, there's this place called hell that you are going to....."

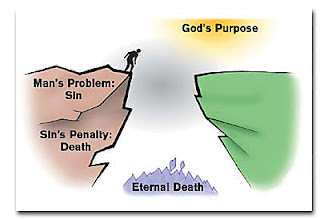

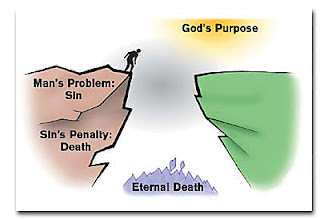

The received gospel that most evangelicals inherited is this: Everyone is going to hell because each individual (no matter who they are or what they have done) is a sinner, thankfully Jesus died for your sins and rose again, you need to now confess you are a sinner and have faith in Jesus so that you are no longer a hell-bound sinner. In most evangelistic presentations (and this is a crucial point), the emphasis is on the gap between God and human beings. Each individual is responsible for "repenting," "having faith," feeling really really guilty and bad, or responding in some way ("having faith," perhaps?) that will close this gap. Some gospel tracts illustrate this by showing a cross that bridges the gap. Your job is to walk across this cross that bridges the great divide.

The received gospel that most evangelicals inherited is this: Everyone is going to hell because each individual (no matter who they are or what they have done) is a sinner, thankfully Jesus died for your sins and rose again, you need to now confess you are a sinner and have faith in Jesus so that you are no longer a hell-bound sinner. In most evangelistic presentations (and this is a crucial point), the emphasis is on the gap between God and human beings. Each individual is responsible for "repenting," "having faith," feeling really really guilty and bad, or responding in some way ("having faith," perhaps?) that will close this gap. Some gospel tracts illustrate this by showing a cross that bridges the gap. Your job is to walk across this cross that bridges the great divide.

Most "biblical evidence" for this received gospel is based on cutting and pasting verses together from various parts of the Bible. This is no accident, because the above gospel is simply not the gospel that Paul teaches. (It is Paul, incidentally, who develops the most thorough New Testament theology of the gospel.) There are verses that one can find to support this gospel, but then again, one can mix and match verses to come to most any conclusion.

Paul's actual gospel spends scant little time (if any) expounding on hell or the sinfulness of individuals. It's there, no doubt, in the classic texts like Romans 1 and Ephesians 2. But the point of such discussions, as I read them, is not to condemn people as much as it is to contrast two approaches to life: one view of life where one is consumed with themselves and ultimately destroyed by their own ego-obsessions, the other view of life is a life lived by faith, walking with the spirit in love (agape) and self-less-ness. It's not really about saving your own self from hell. Actually, this sort of spiritual narcissism ("how can I keep myself from burning in the next life?") is one of the problems.

Paul's gospel is much more progressive. Radically progressive, actually. It is about a "new creation" (2 Corinthians 5:17). It is about "reconciling all things" (Colossians 1:20). Furthermore, contrary to popular evangelistic efforts, the goal is not to elicit a spiritual experience of rebirth. Rather, the goal is to simply recognize that the fact that any person can join the happy band of the redeemed. For Paul, whatever happened on the cross took care of the gulf between God and man. So, living as a part of this merry band of new creationists is to simply recognize that you are already on the other side. The reconciliation has already taken place. There is nothing that a person needs to "do" to cross the bridge. That's been taken care of, which is why Paul spends most of his time talking about what it means to live out this new life, rather than talking about what we have to do to "get in" and "be saved."

So, maybe the reason why so many are losing interest in evangelism is because they never really had a very good gospel. And perhaps I can even be a bit more radical here: perhaps evangelism isn't about proselytizing. Perhaps it isn't about winning converts or "getting people saved." Maybe the great proclamation is simply to announce that there is no gulf between God and humanity, that God's focus for the world is reconciliation and peace, that personal and global transformation start with a gift of grace that is available to all, and that we need as many people as possible to get on board with this positive mission of reconciliation.

It's no wonder evangelism is petering out, or being relegated, impersonally, to mass media proselytizing. It's a dour, powerless gospel. Remember how Paul begins his letter to the Romans? "For I am not ashamed of the gospel, for it is the power of God for the deliverance (soterian) of all who believe." This is a racial inclusivity, not an exclusive who's-in-and-who's-out approach. In Paul's letter to the Galatians power and transformation are also the focus. The life of the spirit produces the fruit of the spirit: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control.

Perhaps evangelistic zeal could be rekindled if a gospel was proclaimed that was a bit more in line with the radical vision of Paul. What is the radical vision? Simply that there is nothing to do, nothing to do to cross a bridge or any such nonesense. Grace is the ultimate do-nothing, which paradoxically transforms. There is nothing to do except to believe in a new creation and live by this faith. This gospel must be beyond formulas, beyond definition, and even beyond words. This is so because the gospel is about grace, which is ineffable.

So, as I read the first verses of Galatians and as I reflect on the state of evangelism today, the pivotal question that arises, the absolutely crucial question for a Christian, is this: have we got the right Gospel?

I have been reading through the Walter Isaacson biography of Albert Einstein. I am about halfway through, and I have enjoyed the read. It has helped me familiarize myself a bit better with the scientific transition from a Newtonian universe to an Einsteinian (if we can call it that) universe. For those interested in Einstein or the scientific advances of his time, I highly recommend this biography.

I have been reading through the Walter Isaacson biography of Albert Einstein. I am about halfway through, and I have enjoyed the read. It has helped me familiarize myself a bit better with the scientific transition from a Newtonian universe to an Einsteinian (if we can call it that) universe. For those interested in Einstein or the scientific advances of his time, I highly recommend this biography.